Thinking in Triangular Numbers

A small case for alternatives to 4s, Fibonacci, and beyond.

—

I was recently inspired by Luis Ouriach’s article exploring Fibonacci numbers as an alternative to 4px spacing. It’s a move that resonates with a lot of us who are tired of arbitrary number sequences in design systems.

But while Fibonacci’s got style, I’ve been diving into something a little less wild: triangular numbers.

Why Use Sequences at All?

Preset number sequences do more than add mathematical flair – they limit choice, in a good way. They steer you away from the rabbit hole of endless values and toward consistent spacing, sizing, and scaling. And unlike ad-hoc or eyeballed scales, number sequences are rooted in something objective. Less preference, more pattern.

Color Modulation

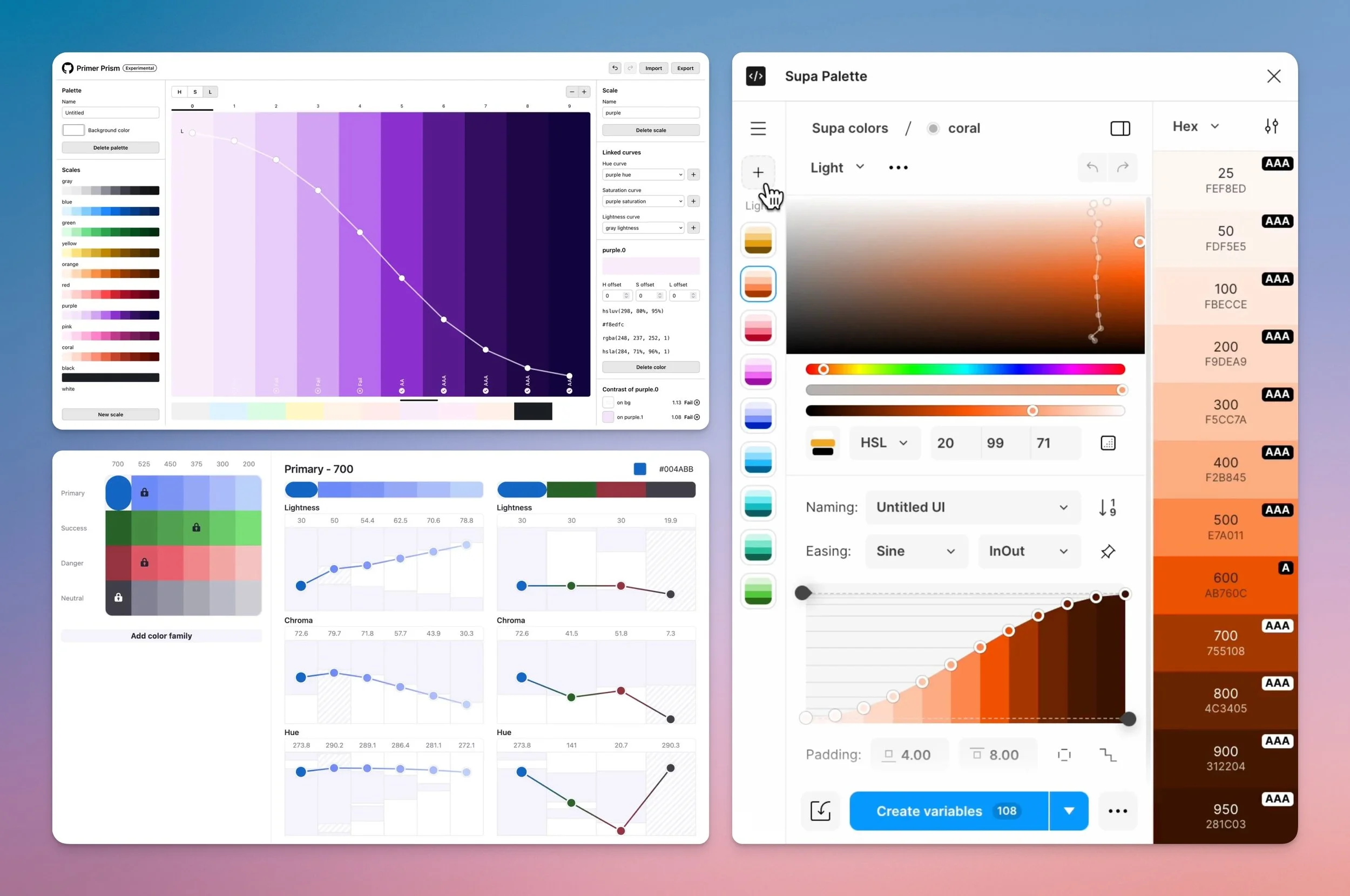

Color palettes are also sequences of numbers across hue, saturation, and brightness. Design systems use mathematical formulas or easing curves to define color ramps, ensuring smoother transitions and more meaningful semantic mapping. Instead of picking arbitrary steps between, say, blue-50 or blue-900, you plot values along defined curves. The result is a ramp that’s intentional, reusable, and adaptable across color modes and brand themes.

Tools like Primer Prism, Atmos, and Supa Palette let you define curves for hue, saturation, and brightness.

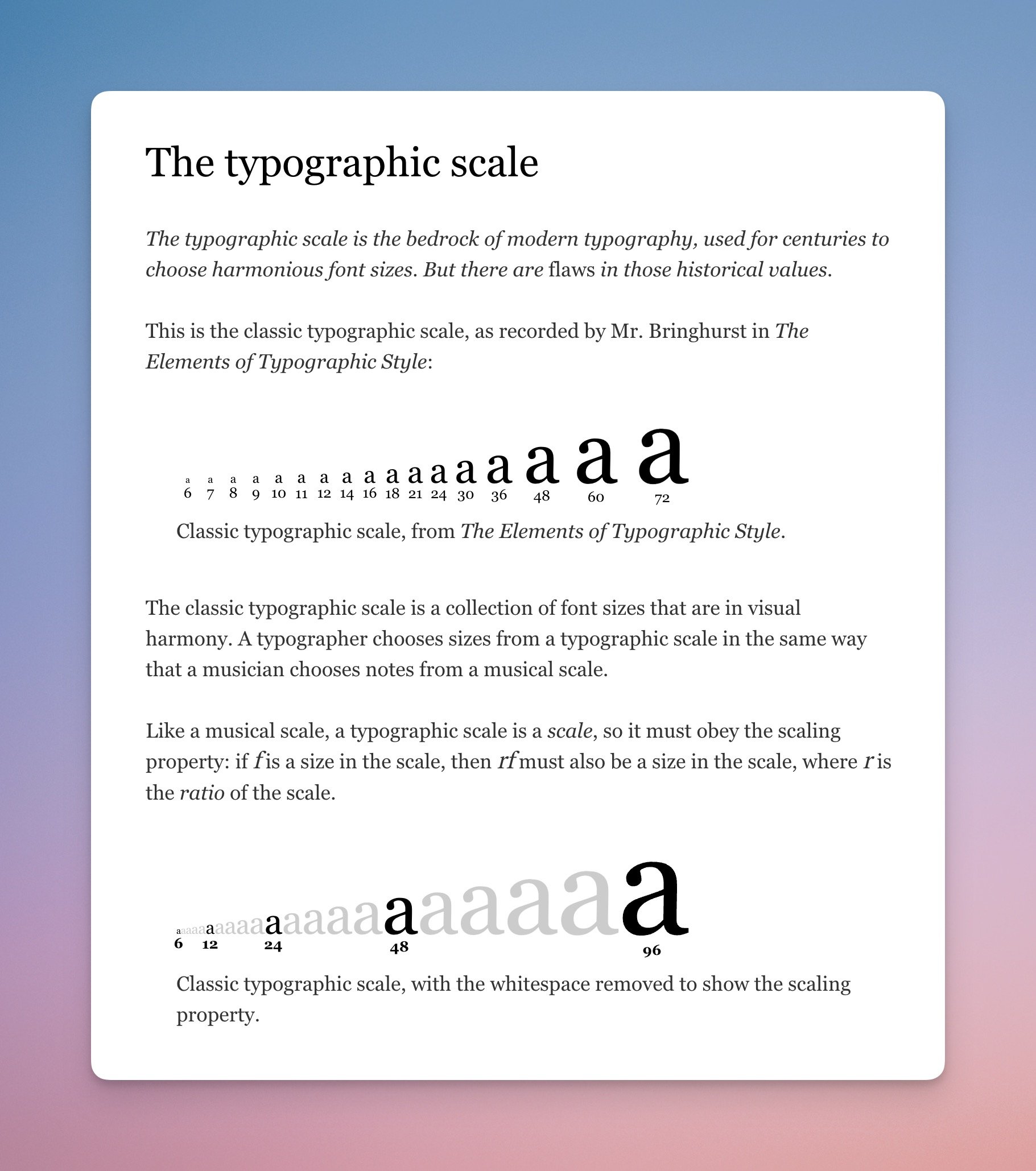

Typographic Rhythm

Traditional typography had its own rhythm long before digital tools. Books like The Elements of Typographic Style reference historical point sizes such as Pica, Brevier, and Minion – a mix of aesthetic judgment and typesetting constraints. While not always mathematically regular, these sizes carried names and values that implied hierarchy and usability.

| Name (American) | Point | Pixel | REM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Double Canon | 56 | 74.67 | 4.666 |

| Canon | 48 | 64 | 4 |

| Double Great Primer | 36 | 48 | 3 |

| Double English | 28 | 37.33 | 2.333 |

| Double Pica | 24 | 32 | 2 |

| Paragon | 20 | 26.67 | 1.67 |

| Great Primer | 18 | 24 | 1.5 |

| Columbian Exchange | 16 | 21.33 | 1.33 |

| Gros Texte | 15 | 20 | 1.25 |

| English | 14 | 18.67 | 1.167 |

| Pica | 12 | 16 | 1.000 |

| Small Pica | 11 | 14.67 | 0.916 |

| Long Primer | 10 | 13.33 | 0.833 |

| Bourgeois | 9 | 12 | 0.75 |

| Brevier | 8 | 10.67 | 0.67 |

| Petite Texte | 7.5 | 10 | 0.625 |

| Minion | 7 | 9.33 | 0.583 |

There’s something charming about these classical names. They hint at a system, but one built more on legacy than logic. You’ll spot small arithmetic patterns here and there, but overall, it’s more cultural than mathematical. Still, it shows how we’ve always tried to make typography scalable and memorable.

That legacy still shapes how we think about type today. Modern design systems have borrowed from musical scales, modular type ramps, and even golden ratios. Spencer Mortensen’s guide on typographic scales is a great deep dive into these methods and how they apply to design systems.

Fibonacci Is Cool (Until It Isn’t)

Fibonacci’s appeal is obvious. And timeless.

A sequence born from nature itself: shells, sunflowers, pinecones, galaxies. It’s poetic math. Each number is the sum of the two before it, and the farther you go, the more it approximates the golden ratio – that elusive proportion designers have chased for centuries.

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89...

But as elegant as it is, Fibonacci can be unruly in practice. It starts off too slow, then gets dramatically fast. That exponential growth means that later steps leap ahead – great for nature, tricky for UI spacing. When you’re trying to build a consistent scale for padding, grid, or component sizing, that jump from 21 to 34 to 55 can feel like too much too soon.

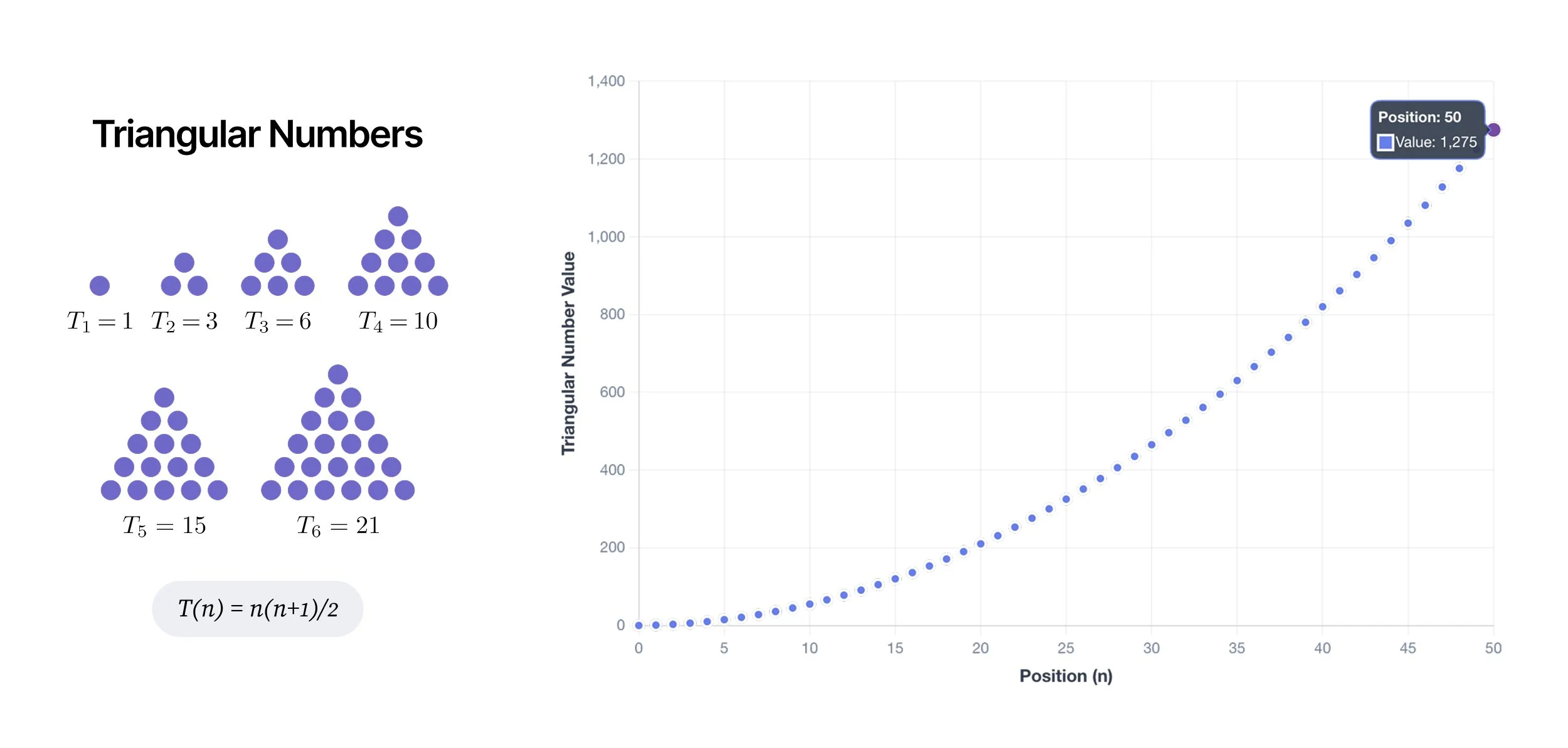

Enter: Polygonal Numbers

When you arrange numbers around geometric shapes, you get polygonal numbers. Triangular (1, 3, 6, 10…), square (1, 4, 9, 16…), and even pentagonal or hexagonal numbers offer new ways to structure a scale. They grow more slowly than exponential sequences and feel more usable across a wider range, offering a consistent rhythm with a hint of mathematical poetry.

For me, triangular sequences are the most usable. They’re called triangular because you can literally arrange them into perfect triangles:

1 dot makes a single point.

Add 2 more, you get a triangle of 3.

Add 3 more, it becomes 6.

Then 4 more for 10, and so on.

Triangular numbers start with a natural ease-in and hold a steady rhythm as they grow.

Each number is the sum of the integers before it. They still scale, but without sprinting away. It’s a sequence that feels natural and progressive – a kind of built-in easing. And for design systems, that hits a sweet spot between rational and usable.

Here’s the comparison at a glance:

Fibonacci: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233…

Triangular: 0, 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, 21, 28, 36, 45, 55, 66, 78, 91…

Notice how Fibonacci starts off too tight, barely usable in the early steps. It finds a sweet spot around 8, 13, and 21 – then shoots off to the moon! The jump from 55 to 89 to 144? Not exactly ideal for UI spacing.

Triangular numbers, on the other hand, give you a practical, scalable rhythm from the start. Each step adds a bit more than the last, but never explodes. You get a steady curve that keeps working even as values grow, which is perfect for spacing, padding, or any scale that needs to stay grounded.

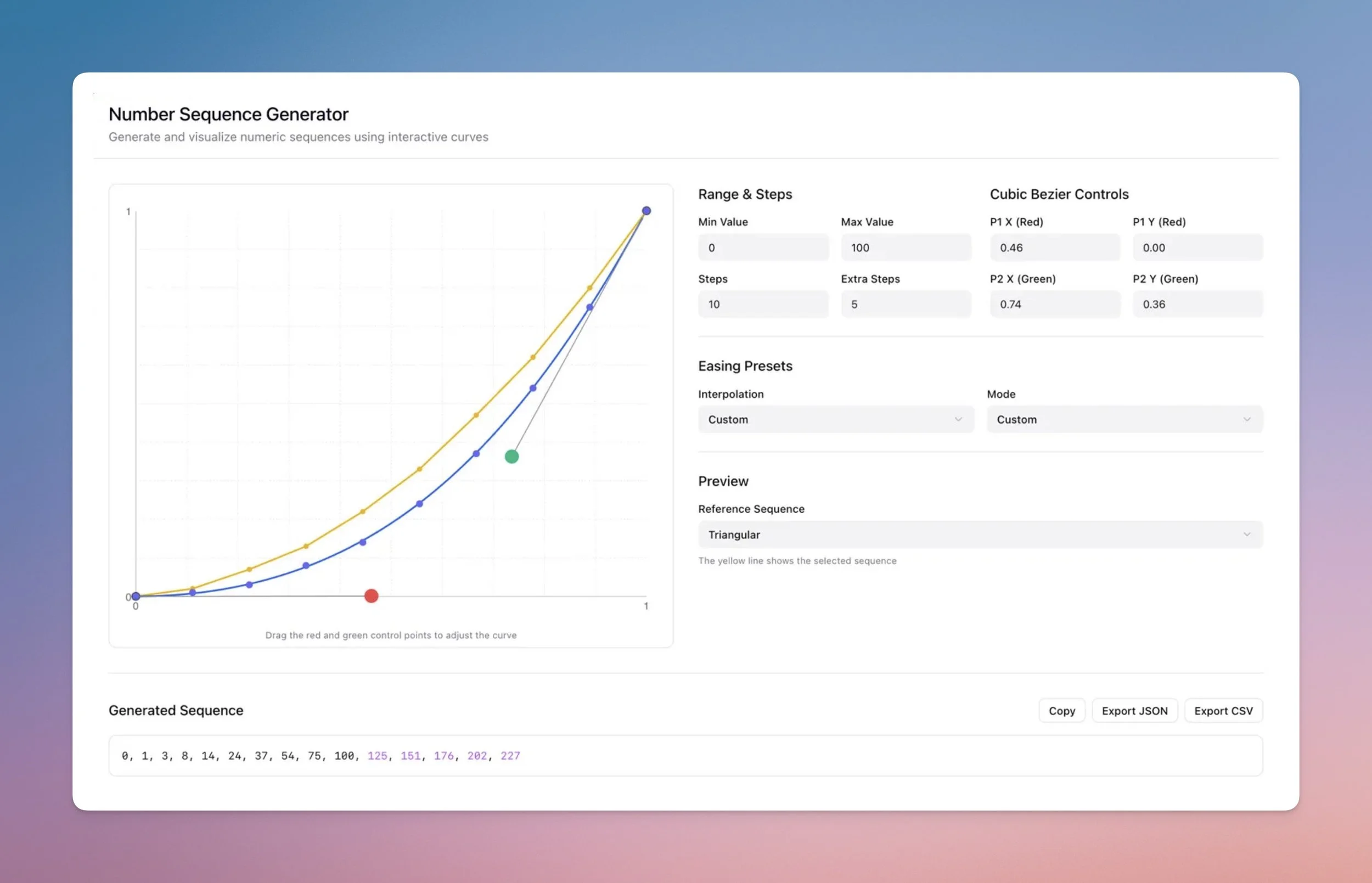

A Tool for Sequence Exploration

To make it easier to explore sequences more freely, I started building a Number Sequence Generator in Figma Make.

It helps me generate and visualize numeric sequences using custom curves or preset math patterns: Fibonacci, triangular, primes, and more. You can adjust cubic Bézier points, preview curve behavior, compare to standard sequences, and export the final array as JSON or CSV for use in spacing, color ramps, motion timing…

It’s a nerdy playground at this point. Just the right mix of math and feel.

A visual playground for generating number sequences. Because, why not?

Let the Universe Handle the Math

The deeper I go into systems, the more I realize: a good system doesn’t just standardize. It liberates you from having to decide. Fibonacci, triangular, geometric, prime… these sequences already carry rhythm, proportion, and balance. We’re not inventing structure. We’re choosing which one to borrow.

The universe already did the hard part. We just need to pick our favorite flavor of math.